Κείμενο

Σήμερα θα σας μιλήσω για μία μελέτη που αρχικά θα σας φανεί ασύνδετη με θέματα διατροφής, αλλά όχι απλά είναι πάρα πολύ σχετική, θα έλεγα ότι είναι μία μελέτη που αναδεικνύει το σημαντικότερο πρόβλημα που αντιμετωπίζω στα δύο κέντρα ιατρικής διατροφολογίας που ηγούμαι. Κάντε υπομονή. Θα ακούσετε κάτι πολύ σημαντικό. Η μελέτη έγινε στις αρχές της δεκαετίας του ‘70, σε ένα από τα διασημότερα πανεπιστήμια στον κόσμο, το πανεπιστήμιο του Princeton στην Αμερική. Οι συμμετέχοντες της μελέτης, που δεν γνώριζαν το σκοπό της, ήταν φοιτητές της θεολογικής σχολής του Princeton που σπούδασαν με σκοπό να γίνουν ιερείς. Μάλιστα, με τέτοιο βιογραφικό είναι σίγουρο ότι οι περισσότεροι αλλά θα έφταναν πολύ ψηλά στην ιεραρχία του ιερατείου της Αμερικής. Στην αρχή της μελέτης οι φοιτητές συγκεντρώθηκαν σε μία αίθουσα όπου τους έδωσαν να συμπληρώσουν κάποια ερωτηματολόγια που αξιολογούσαν αν κάποιος ήθελε να γίνει ιερέας από εσωτερικό, βαθύ κίνητρο, ή τα κίνητρα του ήταν εξωτερικά. Για παράδειγμα, στην ερώτηση “θέλω να γίνω ιερέας για να κάνω καλό στον κόσμο” απαντούσαν περισσότερο θετικά αυτοί που είχαν ισχυρό εσωτερικό κίνητρό, ενώ στην ερώτηση “θέλω να γίνω ιερέας για να πάω στον παράδεισο” αυτοί που οι ερευνητές θεώρησαν ότι τα κίνητρά τους ήταν κυρίως εξωτερικά. Κρατήστε το αυτό στο μυαλό σας. Γιατί παίζει μεγάλη σημασία. Αφού ολοκληρώθηκε η διαδικασία με την συμπλήρωση των ερωτηματολογίων, οι συμμετέχοντες πήγαν ένας-ένας σε ένα διαφορετικό δωμάτιο. Ο σκοπός ήταν να ετοιμάσουν ένα κήρυγμα εμπνευσμένο από την παραβολή του καλού σαμαρείτη. Θυμίζω ότι η παραβολή του καλού σαμαρείτη αφορά έναν άνθρωπο πού βρίσκεται τραυματισμένος στο έδαφος από ληστές και δεν τον βοηθάει κανείς, αλλά μόνο ο καλός Σαμαρείτης. Όταν ολοκληρώνουν την προετοιμασία τους κηρύγματος, οι συμμετέχοντες πρέπει να πάνε σε μία αίθουσα να κάνουν το κήρυγμα. Όσο βρίσκονται στην αίθουσα προετοιμασίας, ένας ερευνητής μπαίνει στην αίθουσα και εδώ αρχίζει και φαίνεται ο σκοπός του πειράματος. Οι συμμετέχοντες

έχουν χωριστεί στην τύχη σε τρεις ομάδες. Στους συμμετέχοντες της μιας ομάδας ο ερευνητής λέει: “Έχεις αρκετό χρόνο. Μη βιάζεσαι. Καλό όμως είναι να ξεκινήσεις σιγά-σιγά για να έχεις την άνεση σου”. Στους συμμετέχοντες της δεύτερης ομάδας λέει: “Προλαβαίνεις, αλλά πρέπει να ξεκινήσεις τώρα για να είσαι στην ώρα σου”. Ενώ στους συμμετέχοντες της τρίτης ομάδας λέει: “ Έχεις αργήσει! Πρέπει να βιαστείς για να είσαι στην ώρα σου! Φύγε τώρα!” Στη διαδρομή που οι συμμετέχοντες πήγαιναν στην αίθουσα που θα έκαναν το κήρυγμα έπρεπε να περάσουν από ένα πολύ στενό διάδρομο, λίγο περισσότερο από ένα μέτρο πλάτος, που οι ερευνητές είχαν σκηνοθετήσει την παραβολή του καλού Σαμαρείτη. Ένας ηθοποιός ήταν ξαπλωμένος κάθετα στο διάδρομο, κλείνοντας όλο το χώρο. Πάνω του είχαν βάλει κόκκινο χρώμα, ώστε να μοιάζει με αίμα και ζητούσε απελπισμένα βοήθεια από τους συμμετέχοντες που ένας-ένας τον πλησίαζαν. Σταματήστε για 1 δευτερόλεπτο και φανταστείτε αυτή τη σκηνή. Φοιτητές θεολογίας που ενώ βρίσκονται στο δρόμο για να κάνουν κήρυγμα για την παραβολή του καλού σαμαρείτη, εμφανίζεται μπροστά τους ένας τραυματισμένος άνθρωπος να τους ζητάει βοήθεια. Οι ερευνητές μέτρησαν πόσοι σταμάτησαν. Το αστείο είναι ότι οι συμμετέχοντες για να προχωρήσουν στο διάδρομο έπρεπε πραγματικά να περάσουν πάνω από τον τραυματισμένο άνθρωπο, πραγματικά σχεδόν πατώντας τον! Είμαι σίγουρος ότι αναρωτιέστε πόσοι σταμάτησαν να βοηθήσουν από την κάθε ομάδα. Πάμε να δούμε. Από την ομάδα των φοιτητών που είχαν άπλετο χρόνο μπροστά τους, σταμάτησε το 63% για να βοηθήσει. Που σημαίνει ότι το 37% δεν σταμάτησε. Σίγουρα θα έπρεπε να μας προβληματίζει. Από την ομάδα των συμμετεχόντων που ήταν στην ώρα τους σταμάτησε το 45%. Από την ομάδα των συμμετεχόντων που ήταν πιεσμένοι από τον χρόνο σταμάτησε μόλις 1 στους 10. Δηλαδή, 9 στους 10 σχεδόν πάτησε και πέρασε από πάνω από ένα τραυματισμένο άνθρωπο για να προλάβει να πάει να κάνει κήρυγμα για το πόσο σημαντικό είναι να σταματάμε και να βοηθάμε τους συνανθρώπους μας

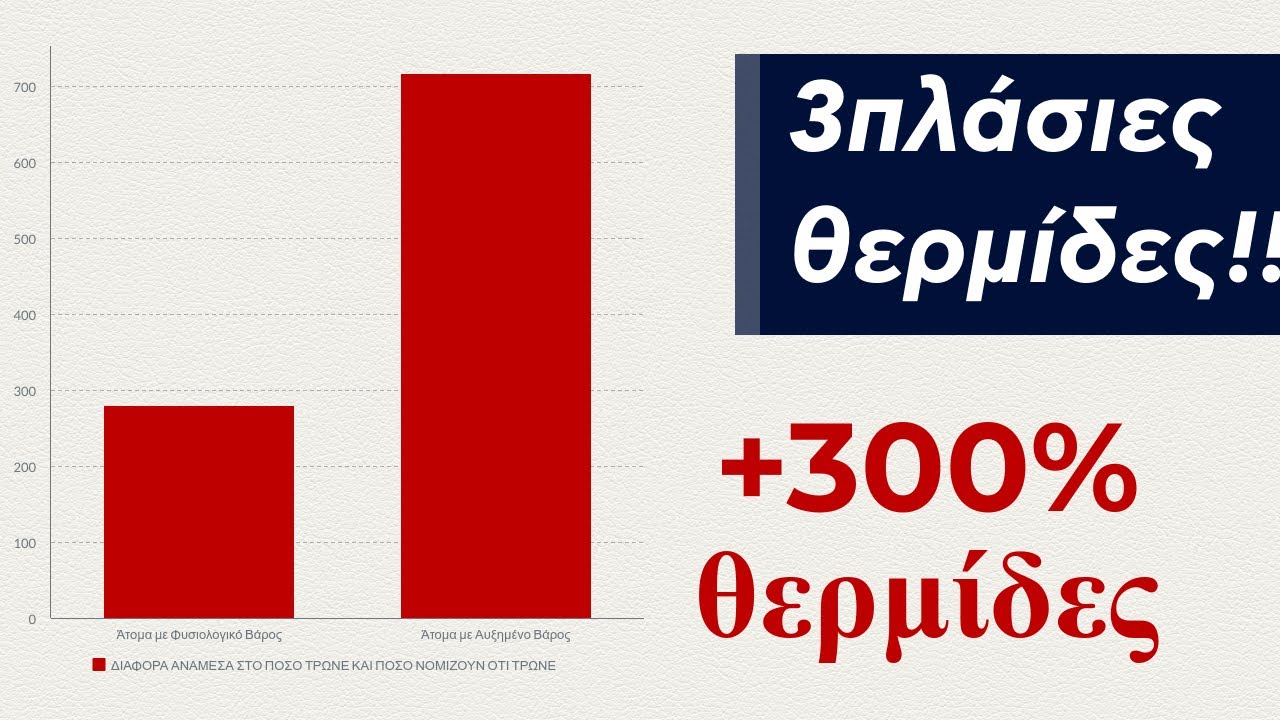

όταν μας έχουν ανάγκη! Ποιο είναι το νόημα αυτής της μελέτης και τι σχέση έχει με τη διατροφή; Οι ερευνητές σύγκριναν τη συμπεριφορά των συμμετεχόντων που δήλωσαν ότι βρίσκονται στην εκκλησιαστική σχολή από εσωτερικό κίνητρο και δεν είδαν καμία διαφορά στη συμπεριφορά. Ακόμα και αυτοί που ήθελαν να δουν το καλό στον κόσμο δεν σταμάτησαν συχνότερα. Αυτοί που σταμάτησαν συχνότερα ήταν αυτοί που είχαν περισσότερο χρόνο. Οι ερευνητές ουσιαστικά προσπαθούν να μας πουν ότι οι επιλογές μας δεν έχουν να κάνουν με το αν είμαστε καλοί ή κακοί άνθρωποι, αλλά με το αν πιστεύουμε ότι έχουμε ή δεν έχουμε χρόνο. Και τονίζω το “πιστεύουμε”. Αλλά και πάλι ίσως μερικοί από σας να μην είστε σίγουροι ακόμα τι σχέση έχει αυτό με τη διατροφή. Ο συχνότερος λόγος που ακούω ότι κάποιος τρώει τροφές χαμηλής ποιότητας είναι ότι δεν έχει χρόνο να φροντίσει τη διατροφή του. Στα δύο κέντρα ιατρικής διατροφολογίας που ηγούμαι έχω παρακολουθήσει δεκάδες χιλιάδες ανθρώπους που θέλουν να βοηθηθούν στο να βελτιώσουν τη διατροφή τους και ίσως η συχνότερη δικαιολογία που δίνουν στον εαυτό τους για να καταναλώνουν τροφές χαμηλής διατροφικής αξίας είναι η έλλειψη χρόνου. Πιστεύουν ότι δεν προλαβαίνουν να φροντίσουν τη διατροφή τους. Εσείς προλαβαίνετε να φροντίσετε τη διατροφή σας; Πόσο συχνά σας κυνηγάει ο χρόνος και πιστεύεται ότι “αναγκάζεστε” να αρπάξετε ένα νόστιμο σουβλάκι αντί να αφιερώσετε 15 λεπτά να φτιάξετε φακές στη χύτρα ταχύτητας;

0 Σχόλια